Some of us are rejoicing as we reopen our adjusted massage therapy practices to COVID-19 realities. Others reopened and now have reclosed their practices as infection rates soar across the United States. Many of us are not ready to go back or are still restricted by local and/or state health mandates. Whatever your status, it is imperative you get ready for that next client—whether that’s tomorrow or next month—and be prepared for how to work with them during the new circumstances brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic. For those therapists who work with prenatal and postpartum clients, this is especially important.

First though, a note: This article will NOT be covering necessary changes to your environment, policies, information collection, hygiene, etc., that are so thoroughly discussed elsewhere. ABMP has informative, practical input for you on their website,1 as do most state associations and credentialing agencies. Also, stay current with the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA),2 the National Institutes of Health,3 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC),4 and your local jurisdictions for up-to-date guidance relevant to massage therapy).

Some of these agencies offer evolving data on the pandemic’s specific impact during pregnancy, labor, and postpartum. I have combined information from these agencies and from Evidence Based Birth,5 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists,6 Midwives Alliance of North America,7 the CDC, and other comparable agencies in other countries, resulting in a well-rounded perspective on COVID-19 and childbearing.

From these sources during late July 2020, it appears that:

- Pregnant women with COVID-19 may be more likely than nonpregnant women with COVID-19 to need care in an intensive care unit (ICU) or need a ventilator (for breathing support).

- Pregnant women who are Black, Hispanic, or Asian may have a higher risk of severe illness or need ICU care more often than other pregnant women. This is likely caused by social and economic inequity, not biological differences.

- Although the risk of needing more care in the hospital and having more severe illness may be increased, the overall risk of these outcomes is still low for pregnant women.

- The risk of death is not higher for pregnant women with COVID-19 than for nonpregnant women with COVID-19.

- Some pregnant women with COVID-19 have had preterm births, but it is not clear whether the preterm births were because of COVID-19.

- Researchers have found a few cases of COVID-19 that may have passed to a fetus during pregnancy, but this seems to be rare.

While some of this information is reassuring, pregnant women are disproportionately affected by respiratory illnesses in general, and thus they may be at higher risk for contracting COVID-19. Managing your practice hygiene then is critical.

Physiological and mechanical changes in pregnancy increase susceptibility to infections in general, particularly when the cardiorespiratory system is affected, and encourage rapid progression to respiratory failure.8 As data gradually emerge regarding the effects of COVID-19 infection on pregnant, birthing, and postpartum people, the implications for us when they become our clients evolves too, and it is likely to remain ambiguous and incomplete. If you are seeing childbearing massage therapy clients, staying currently informed is an ethical imperative.

Not So Fast to the Treatment Room

Coronavirus or not, pregnancy’s common companions of back, pelvic, and hip pain continue to bring clients seeking relief from our work. And the additional stress of the pandemic for those expecting a baby can be overwhelming. Regardless of need, any expectant clients with COVID-19 symptoms, presumed or suspected infection, or positive test results should not be receiving massage therapy while ill or contagious. If they had credible exposure, they should undergo 14 days of isolation to prevent spread if they are infected. Because of the varied severity of symptoms and recovery time, best practice is to seek medical or midwifery review of every pregnant client’s unique condition and request any massage therapy limitations or contraindications specific to that person. Even with that clearance, you may want to delay for at least three months after illness.

Unfortunately, with the high rate of asymptomatic infection and the testing limitations, your clients and/or you may or may not be infected at any point in your treatment interactions. Consequently, I believe it is most responsible to modify all maternity massage therapy protocols as though each expectant or new-mother client has, or has had, this infection. Adaptations for respiratory and placental efficiency and the prevalence of blood clots have always been critical factors with pregnant and postpartum massage therapy clients, even prior to the emergence of the coronavirus. COVID-19 appears to increase these concerns significantly. Let’s next consider these respiratory, positioning, and blood-clotting factors and the ramifications for safe practice.

Respiration, Placental Function, and Positioning

A common, though not universal, symptom of COVID-19 is shortness of breath. As a result, be sure to assess and think through positioning’s effect on maternal and fetal oxygenation for each individual. Common nursing practice9 and obstetrical research10 point to side-lying positioning during pregnancy, left or right, resulting in better maternal and fetal oxygenation and outcomes when compared to other positions. There is a slight advantage to the left side-lying position over the right that, in normally progressing pregnancies, is usually irrelevant.

With coronavirus, however, a recent small study showed some negative effects and compromise in placental functioning when expectant people are infected.11 As of yet, there is no data regarding how long after infection this reduction in placental function may last.

Recommended Side-Lying Positioning Guidelines

With these considerations in mind, I now recommend the following regarding side-lying positioning:

- Use left side-lying exclusively or for most of a given session, especially if other respiratory compromises are evident, such as shortness of breath (not illness related), postural breathing restrictions, or obesity; asthma, respiratory allergies, or a cold; multiple gestation; other placental abnormalities; or gestational hypertensive disorders (Image 1).

- Use left and right side-lying positioning with clients who do NOT have any of the compromises listed above and whose pregnancies are proceeding normally.

- After COVID-19 recovery, continue using left side-lying exclusively, or almost exclusively, unless you consult with the client’s physician or midwife for other positioning clearance, since ongoing placental effects are still undetermined.

Recommended Supine Positioning Guidelines

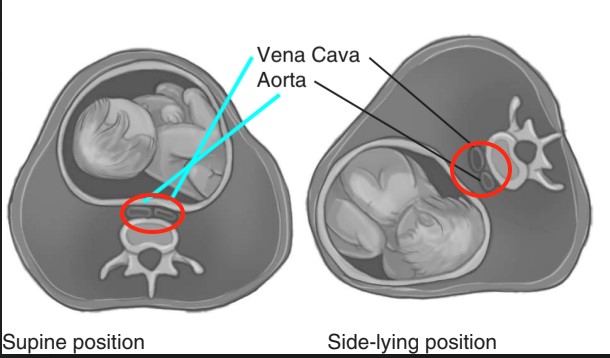

If you work with a pregnant client in the supine position, then prevention of supine hypotensive syndrome is of increased importance, especially since your client may be asymptomatic and/or untested. Supine hypotensive syndrome is decreased blood pressure caused by the enlarged uterus compressing the inferior vena cava sufficiently to reduce venous return. Symptoms include uneasiness, dizziness, weakness, nausea, shortness of breath, or other discomforts when clients are lying flat on their back, although some report no symptoms (Image 2).

I recommend a strict adherence to the following positioning guidelines for all your pregnant clients.

- Limit any supine time to 3–5 minutes if you do not make one of these positioning adaptations.

- From weeks 13 to 22, adapt supine positioning by placing a wedge under the client’s right lower torso for singleton gestation; after 12 weeks with multiples (Image 3).

- After 22 weeks, only use semi-reclining and side-lying positions (Image 4).

If you are well-trained to work with pregnant clients, then providing stable, aligned positioning in side-lying, supine, or semi-reclining is second nature to you. Of course, those therapists already skilled in side-lying positioning will also have that side-lying advantage with all clients, providing an alternative that keeps therapist and client from breathing face-to-face as necessitated when the client is supine.

Blood Clot Considerations

Changes in clot-dissolving capacity occur in all pregnancies and are a normal and protective adaptation to avoid birth and postpartum hemorrhage. Safe perinatal massage therapy always requires taking precautions relevant to possible blood clots. Research points to approximately double the coagulation activity during pregnancy when compared to nonpregnant women, and a tendency toward formation of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) where clots form in the inguinal, femoral, and saphenous veins.12 DVT is even more common postpartum, particularly for those who had cesarean births, other surgeries, or who hemorrhaged. Those expectant and postpartum individuals who are on bed rest are especially prone to clot production; that risk also exists for people who smoke, are over 35 years old, have varicose veins, have recently used birth control pills, are obese, have lupus, have been pregnant multiple times before, or are carrying multiples.

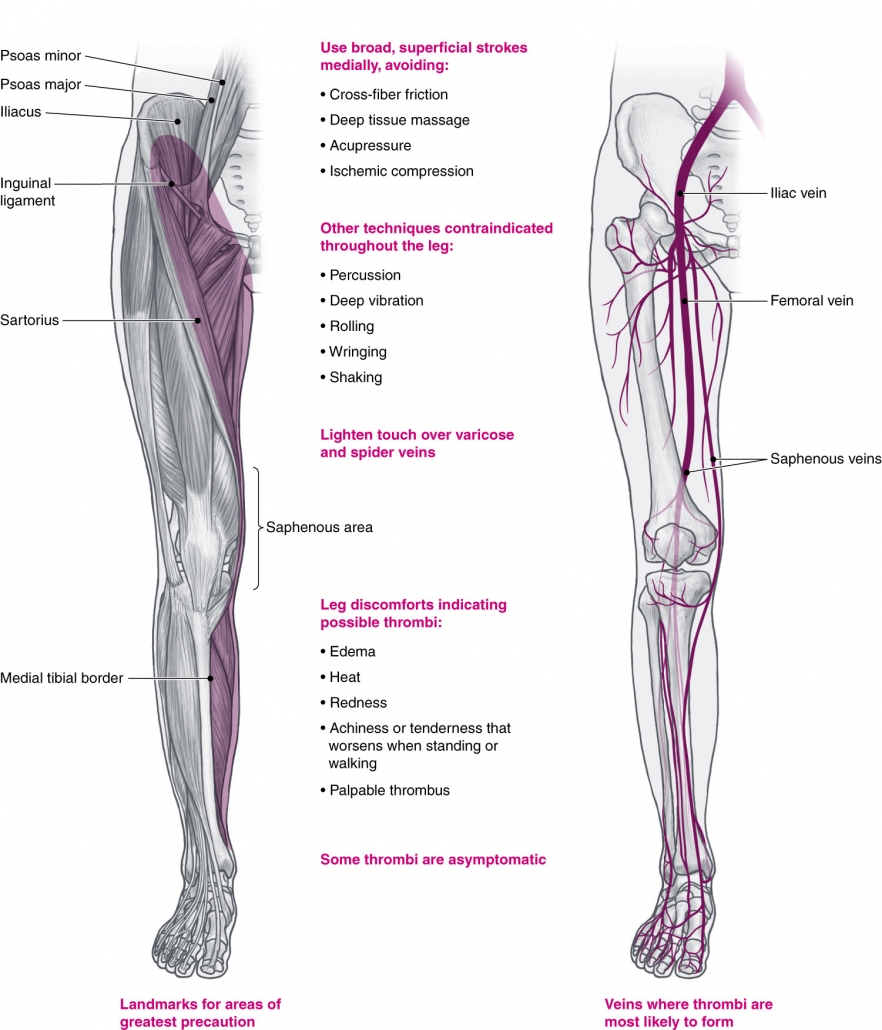

If you are not fully educated about the physiology of normal and high-risk pregnancy- and postpartum-related hypercoagulation and guidelines to reduce chances of thrombi moving from the legs into general circulation during pregnancy and early postpartum, now’s the time to learn, and wait to work with these clients until you do. The accompanying illustration offers a very quick review of the most relevant massage therapy adaptations to reduce complications related to hypercoagulation during pregnancy, especially those relevant for the legs (Image 5). Do not consider looking at this image as adequate education on this critical topic.

The restrictions summarized in this illustration are aimed to reduce possible pulmonary embolisms (clots that have traveled from elsewhere that obstruct vessels in the lungs). It is critical you follow thesefor ALL prenatal and postpartum massage therapy clients, regardless of COVID-19. Of course, you alsoshould observe your clients for any of the characteristic symptoms of leg thrombi—increased edema in the foot and/or leg (often unilaterally), localized swelling, heat, redness, and painful, achy legs that can be tender with palpable, ropy veins. These symptoms are particularly worrisome if they increase when your client walks. But to be clear, legs that are painful or achy are a hallmark of pregnancy, so these symptoms alone do not guarantee a blood clot. A clear determination of the presence of clots is also difficult because thrombi are often asymptomatic.13 Given the increased likelihood that blood will coagulate in pregnancy and postpartum, the difficulty in determining the presence of clots, and the potential harm of freely circulating clots, it seems prudent to treat all pregnant and postpartum clients as though they have leg clots. For many decades, pre-coronavirus pandemic, we recommended observing the summarized guidelines in Image 5 throughout pregnancy and with postpartum clients for at least 8–10 weeks after birth. The emerging data about blood clots and COVID-19 is sobering, particularly when added to existing clot dangers during pregnancy and postpartum. Coagulopathy in COVID-19 is a disruption in blood-clotting mechanisms that can appear as organ damage, strokes, heart attacks, pulmonary embolisms, rashes, and COVID-toe, with bumps, swelling or redness as evidence of excessive bleeding and clotting in small vessels (microthrombosis).

Hypercoagulation during and after this illness further reinforces the contraindication that expectant and postpartum clients with COVID-19 symptoms, suspected infection, or positive test results should not be receiving massage therapy while ill or contagious. Furthermore, because of the varied severity of symptoms and recovery time, and the unknowns related to childbearing, I recommend you seek medical or midwifery review of everyone’s unique condition to request any massage therapy limitations or contraindications for that client.

For those cleared for massage therapy, be sure to assess thoroughly for COVID-19 specific manifestations, whether they have had the illness, what was its severity, and any subsequent recovery concerns.

Recommended Blood-Clotting Guidelines

For clients who have had COVID-19 and are seeking massage, these are my best recommendations.

- Most conservative—wait at least three months for any massage

- Less conservative—wait at least three months for any massage of the legs or lower abdomen

- Least conservative—but still probably safe for most within the three-month after-phase: strict adherence to leg massage limitations and guidelines, summarized in Image 5. Most importantly, work superficially (light oil and pressure) on the medial side of the entire leg and into the inguinal area. In addition, be cautious anywhere else major arteries and veins reside, including the neck and axilla, and be judicious about using deep pressure there.

If you do not understand fully the underlying physiological mechanisms and these guidelines, I urge you to delay working with pregnant and postpartum clients until you further educate yourself.

Can Massage Therapy Safely Help?

Absolutely! Despite all these increased precautions and limitations, expectant and postpartum clients may find great relief from skilled massage therapy, beginning with reducing the negative effects of this stress-saturated pandemic.

The following articles fully articulate these concerns as they affect massage therapy in general, and it is critical you understand this information. Read all of them prior to working with pregnant and postpartum clients while COVID-19 is still spreading as part of your “first, do no harm” imperative.

- Article—“COVID-19-Related Coagulopathy: Blood Clotting Through Thick and Thin” by Ruth Werner, www.massageandbodyworkdigital.com/i/1256819-july-august-2020/34

- Blog—“COVID-Related Coagulopathy, Take 3: A Conversation with a Hematologist” by Ruth Werner, www.abmp.com/updates/blog-posts/covid-related-coagulopathy-take-3-conversation-hematologist

- Blog—“Ready to Dive Back In?” by Ruth Werner, www.abmp.com/updates/blog-posts/ready-dive-back

- Interim Guidance—“The WSMTA’s Interim Guidance on Practice Guidelines,”

www.mywsmta.org/resources/Documents/COVID%2019/WSMTA’s%20Interim%20Guidance%20on%20Practice%20Guidelines.pdf

Editor’s note: Portions of this article are excerpted from the third edition of Pre- and Perinatal Massage Therapy by Carole Osborne, Michele Holland, and David M. Lobenstine. Projected publication is December 2020/January 2021 by Handspring Publishing.

Notes

- Associated Bodywork & Massage Professionals, “COVID-19 Updates for the Massage Profession,” accessed July 2020, www.abmp.com/covid-updates.

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration, “Guidance on Preparing Workplaces for COVID-19,” accessed July 2020, www.osha.gov/Publications/OSHA3990.pdf.

- National Institutes of Health, “Special Considerations in Pregnancy and Post-Delivery,” accessed July 2020, www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/special-populations/pregnancy-and-post-delivery.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Considerations for Inpatient Obstetric Healthcare Settings,” accessed July 2020, www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/inpatient-obstetric-healthcare-guidance.html.

- Evidence Based Birth, “Coronavirus COVID-19/Evidence Based Birth Resource Page,” accessed July 2020, www.evidencebasedbirth.com/covid19.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, “Coronavirus (COVID-19), Pregnancy, and Breastfeeding: A Message for Patients,” accessed July 2020, www.acog.org/patient-resources/faqs/pregnancy/coronavirus-pregnancy-and-breastfeeding#How%20does%20COVID19%20affect%20pregnant%20women.

- Midwives Alliance North America, accessed July 2020, www.mana.org.

- P. Dashraath et al., “Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic and Pregnancy,” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 222, no. 6 (June 2020): 521–31, www.ajog.org/article/S0002-9378(20)30343-4/fulltext.

- Susan Ricci, Essentials of Maternity, Newborn, and Women’s Health Nursing, 4th ed. (Baltimore: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2017).

- R. Silver et al., “Prospective Evaluation of Maternal Sleep Position Through 30 Weeks of Gestation and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes,” Obstetrics & Gynecology 134, no. 4 (October 2019): 667–76, https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000003458.

- E. Shanes et al., “Placental Pathology in COVID-19,” American Journal of Clinical Pathology 154, no. 1 (July 2020), https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcp/aqaa089.

- P. Devis and M. G. Knuttinen, “Deep Venous Thrombosis in Pregnancy: Incidence, Pathogenesis and Endovascular Management,” Cardiovascular Diagnosis and Therapy 7 (December 2017): S309–S319,

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5778511. - T. Callahan and A. Caughey, Obstetrics and Gynecology (Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2007).

Fortunately there were several months before I had to sustain four days of teaching. Because my usual focused, productive self only occasionally briefly emerged, I would ride those fleeting times like the wind. Then I would maximize my joy while attending to many languishing work commitments and desires and to seeing a few clients. Often it was the meditative focus of doing a session or teaching a workshop that most grounded me to the Eternal realities rather than being swept off my feet in the emotional tides.

Fortunately there were several months before I had to sustain four days of teaching. Because my usual focused, productive self only occasionally briefly emerged, I would ride those fleeting times like the wind. Then I would maximize my joy while attending to many languishing work commitments and desires and to seeing a few clients. Often it was the meditative focus of doing a session or teaching a workshop that most grounded me to the Eternal realities rather than being swept off my feet in the emotional tides. Andrew Albert Sheets (1948-2016), age 67, set his final sails on May 26, 2016. The hearts of his wife Francine Martinez, his children Josh Sheets, Elizabeth Gladys, and Elizabeth Martinez, his granddaughter Peyton Martinez, and many dear friends and other family will forever harbor his love.

Andrew Albert Sheets (1948-2016), age 67, set his final sails on May 26, 2016. The hearts of his wife Francine Martinez, his children Josh Sheets, Elizabeth Gladys, and Elizabeth Martinez, his granddaughter Peyton Martinez, and many dear friends and other family will forever harbor his love.

Andy also embraced his role as grandfather. His mischief and playfulness with his granddaughter, Peyton, brought a new light to his eyes and a sparkle that will not be forgotten. His enormous bear hugs, tickles and playfulness he shared with Peyton will be passed on to his future grandchildren with zest and accompanied by stories of “Papa”.

Andy also embraced his role as grandfather. His mischief and playfulness with his granddaughter, Peyton, brought a new light to his eyes and a sparkle that will not be forgotten. His enormous bear hugs, tickles and playfulness he shared with Peyton will be passed on to his future grandchildren with zest and accompanied by stories of “Papa”.

HINTS

HINTS imagery

imagery

Refer to image 1 as you apply the following guidelines. When standing beside a massage table, plant your feet firmly on the floor. Spacing your feet shoulders’ width apart and one foot ahead of the other by one to three foot lengths is usually best. Flex your knees. Don’t tire yourself with too deep a stance, but avoid limiting your weight shift and maneuverability with too shallow a stance. You can shift your body weight directly into your working tool if your torso is facing toward the point where you intend to apply pressure. The more direct the vector of pressure applied, the less energy required to achieve effective depth.

Refer to image 1 as you apply the following guidelines. When standing beside a massage table, plant your feet firmly on the floor. Spacing your feet shoulders’ width apart and one foot ahead of the other by one to three foot lengths is usually best. Flex your knees. Don’t tire yourself with too deep a stance, but avoid limiting your weight shift and maneuverability with too shallow a stance. You can shift your body weight directly into your working tool if your torso is facing toward the point where you intend to apply pressure. The more direct the vector of pressure applied, the less energy required to achieve effective depth. Seated Work

Seated Work Your hands need to perceive the needs of the tissue beneath. They perform fine, delicate movements as they direct energy and apply appropriate technique. They sustain the weight of your body as you apply compressions, kneading procedures, or stroking. They are the most important tools of your trade. You must protect the integrity of your elbows, fingers, and wrists. Whatever technique you apply, perform it with as much open, balanced alignment of these joints as possible. If you repeatedly hyperextend your wrist joint during deep palmar and hypothenar strokes, carpal tunnel syndrome, ligament strain in the wrist, and/or tendonitis can result.

Your hands need to perceive the needs of the tissue beneath. They perform fine, delicate movements as they direct energy and apply appropriate technique. They sustain the weight of your body as you apply compressions, kneading procedures, or stroking. They are the most important tools of your trade. You must protect the integrity of your elbows, fingers, and wrists. Whatever technique you apply, perform it with as much open, balanced alignment of these joints as possible. If you repeatedly hyperextend your wrist joint during deep palmar and hypothenar strokes, carpal tunnel syndrome, ligament strain in the wrist, and/or tendonitis can result. Work with both left and right sides of your body so that both hands and arms are equally strong and agile. You can increase control, dexterity, and strength in your hands while enjoying the products and pleasures of activities like playing piano, guitar, or rhythm instruments; typing; or weed pulling. Other more structured exercises include:

Work with both left and right sides of your body so that both hands and arms are equally strong and agile. You can increase control, dexterity, and strength in your hands while enjoying the products and pleasures of activities like playing piano, guitar, or rhythm instruments; typing; or weed pulling. Other more structured exercises include: Core Body Stability—Pectoral Girdle

Core Body Stability—Pectoral Girdle